INTRODUCTION: Every few years a sermon knocks my socks off. This unusual sermon by The Rev. Devon Anderson was heard last Sunday at Trinity Episcopal Church in Excelsior, Minnesota. The text is Luke 3:1-6. Disclaimer: the sources for the sermon are listed at the end; the text itself does not include footnotes and does not always include quotation marks.

___________________

A few weeks ago I was in Baltimore at a church meeting held at the Maritime Institute of Technology’s conference center. The institute teaches how to pilot everything from a tugboat to the biggest of seafaring barge. During our meeting my friend Ernesto discovered that the Maritime Institute boasts two “full mission, ship handling” simulators. With a bit of sweet talk, he finagled a tour.

The simulators are housed inside huge 80X30 feet curved projection screens (kind of like an iMax theater). Inside is constructed an actual bridge – the literal steering wheel, radar, and control panels that any barge of that magnitude would have. We stepped onto the bridge in darkness. But after our guide punched some buttons and threw a few switches, the lights came on and we were – in an instant – ship captains, navigating an industrial barge through Baltimore harbor. Ernesto and I took turns serving as captain and first mate.

At some point our tour guide started to mess with us. “Hmmm…,” he said, “it looks like it’s about to rain.” A few buttons, a few switches, and the sky began to darken, as virtual raindrops misted the windows. “Hmmmm…,” he said again, “I think we’re heading for a bit of a hurricane,” and all of a sudden we were in the open sea gazing back at the Maryland coastline, as the waves swelled, and the barge dipped and rocked deeper and deeper. “Oh no,” said our host, clearly enjoying himself in the face of our growing panic, “it looks like the hurricane knocked out power in Baltimore.” As he said it, the control panel, too, flashed and went cold as the sound of the engines cut out. In an instant everything went black. I mean, really black. Out of the darkness came the voice of our guide, “Hmmm…what are you going to do now?” We drove the barge around in the dark for a while – which was terrifying — as the hurricane subsided. Eventually the click click click of buttons and switches cleared the night sky, and from the darkness emerged a million sparkling stars. “When everything goes dark,” our guide told us, “a good pilot slows down and watches for what can help him.”

Hmmm….I’ve been thinking about that virtual darkness out on the virtual sea these past weeks. Advent always happens in the darkest of days, as our little place on the planet moves further and further away from the sun. This time of year, we know a lot about darkness. Our Advent scriptures reflect that. So much of what we read in Advent is about darkness and our thirst for light. “The Lord is my light and my salvation…(Ps 27:1)” writes the psalmist, “the fountain of life in whose light we see light (Ps 36.9). “The people who walked in darkness have seen a great light; those who lived in a land of deep darkness – on them light has shined.” (Is 9:2). And even today John the Baptist calls the people out into the cold, dark, desert night so they are ready for the light that will save them all. In so many of our Advent stories, the message is the same: the light of the world has come to put an end to darkness, to be a lamp in the hands of those who believe. Like myself, I know so many people whose lives depend on that promise – when we can’t see where we are going; when the bottom drops out; when our prayers go unanswered and we’re marooned in the kind of darkness that makes us afraid to move – we cling to the promise that if we can just keep our minds focused on the light of the world then sooner or later God will send us some bright angels to lead us out.

And yet – deep in our holy scriptures there lives an equal and opposite truth that almost never comes up in church: that God dwells in deep darkness. God comes to the people in dark clouds, dark nights, dark dreams and dark strangers in ways that sometimes scare them half to death but almost always for their good, or at least, for their transformation. God does some of God’s best work in the dark.

We have been conditioned to view darkness as a negative, symbolizing what’s sinister, or dismal, or tragic or wrong. It was a really dark film. We’re in a really dark place right now. He’s gone to the dark side. No one ever asks God for more darkness, please. Please God, come to me in a dark cloud. Give me a dark vision. Please eclipse the sun and throw life as I know it into complete shadow. Put out my lights so I can see what I need to see. Then, send me a dark angel on the worst night of my life, please.

And no one asks for darkness in the Bible, either, but it happens. Once you start noticing how many things happen at night in the Bible, the list grows fast. God comes to Abraham in the dark, instructing a series of desired sacrifices then sealing the covenant with the people Israel forever. God comes to Jacob in the dark not once, but twice – the first in a dream at the foot of a heavenly ladder, and the second on a riverbank where an angel wrestles him all night long. The exodus from Egypt happens at night; God parts the Red Sea at night; manna falls from the sky in the wilderness at night – and that’s just the beginning.

The cloud and the glory always seem to go together – not just in the Hebrew Scriptures, but in our Gospels, too. Ask Jesus’ disciples Peter, James, and John who entered another cloud on another mountain where they too were overshadowed by the glorious, terrifying darkness of God. Ask Saul the ferocious who was blinded on the road so he could be led by the hand to a hard bed in a rented room, where he finally became soft enough to welcome a dark angel named Ananias. Ask Mary how her life – and the life of the whole world – changed when the savior of the world was born in that scary, darkest hour just before dawn. Ask Mary Magdalene who, in her insurmountable grief, discovers the risen Christ. “Early on the first day of the week, while it was still dark…” the discovery of resurrection begins.

It’s not a popular truth, but there it is: God dwells in deep darkness. When we cannot see – when we are not sure where we are going and all our old landmarks have vanished inside the storm – then plenty of us can believe we are lost and forgotten. But what I am asking you to consider is an additional theology – that when we find ourselves in darkness, we may be the exact opposite of lost and forgotten. Based on the witness of those who have gone before, we know that darkness is where God most often restores us when our lives have broken apart. It is the cloud of unknowing where nothing we thought we knew about God can prepare us to meet the God who is. It is in darkness where new life, no matter how shattered, is born.

There are real benefits to this kind of faith, though they may not appeal to those for whom God can only be light (and in whom there is no darkness at all). The first benefit is that we have to slow way, way down when we find ourselves in the dark. When the kids were little we took them to visit Crystal Cave in western Wisconsin, right off I-94. It’s campy as all get-out, but it’s been around as a tourist attraction for a long time, first discovered in 1881. Just like any cave or mine tour, visitors must walk down flight after flight of industrial stairs, down, down, down – 70 feet in this case — into the damp, drippy earth. At some point the guide flips off the lights so everyone can get a feel for how dark the dark can be – like, can’t see your hand in front of your face dark. Anyone that’s been on one of these tours knows – the minute those lights go out, everyone freezes. There’s just no running around in dark like that. All the things we pride ourselves on in the light outside – our speed, our agility, our ability to talk fast and get things done – they don’t help us one single bit in that kind of darkness. Darkness forces us to slow down and use senses we don’t use when our eyes are working in the light of day. Darkness like that sharpens our senses, hones our awareness, makes us hyper-sensitive to God’s light touch.

Another benefit of faith in darkness is teaches that none of our outside navigational tools can, in the end, really help us. Just like when the power went out in the virtual Baltimore harbor – when we hit real darkness, external things we depend upon in the light of our normal lives to keep us safe and secure, no longer work. If it’s not already inside us, then it’s of limited use to us in the dark places. Once we enter darkness we find out what our primary resources are: love, hope, vulnerability, openness, and what insistent, sacred whisper we can learn to trust when we’re navigating by faith and not by sight. We learn in that place to trust more supremely what only God can do for us, over what we think we can do for ourselves.

And finally, inside darkness with everything slooooowed waaaay doooowwn, depending on what’s inside ourselves to feel our way forward, the good news is that God has room and time and enough of our attention to bring forth new life – an entirely new thing that didn’t exist before dark descended. One of my favorite paintings of all time is from Van Gogh’s olive tree series, housed in the permanent collection of the Minnesota Institute of Arts. A light, lavender punctuates the painting in rows between trees and in the background mountain scape. Apparently Van Gogh considered the lavender a color of “consolation” (his word) in that he felt the color was not its own entity, but created by the stormy confrontation of darkness weakened by light. The new creation only possible because of darkness.

I know my defense of darkness will never, ultimately, sell. Endarkenment is never going to appeal to anyone the way enlightenment does. But for those who are already sitting in the dark, and for those of us who know that at some point we’ll be there, too, to consider the possibility that God dwells there with us is Gospel Good News indeed. And, in the end, I do know this: the thing about the cloud of unknowing, which even the saints take on trust is that it’s not there to get through like a test or a fever. It is God’s home. It is the place where God dwells. To be invited in is a great honor, and to stay awhile? Better yet. When sitting in darkness, we never feel that it’s a great honor – it’s the last place any of us want to be. But I do know this: that for those who make it out the other side, while they may not have a lot of words to describe where they have been, and they’ll tell us they never would have chosen it in a million years – they do have a great story to tell and more than not it’s a story that includes redemption and healing, regeneration and a new wisdom. They might just tell us that now that it has happened they would never give it back. AMEN.

Sources:

The brilliant idea and direct quotes about God doing God’s best work in the dark are excerpted from Barbara Brown Taylor’s Learning to Walk in the Dark (2014), an excellent read that I highly recommend.

The Maritime Institute of Technology’s website (click HERE) has interesting information about its simulator-based training programs.

Van Gogh’s approach to the cover lavender is commented upon by Goethe in the book Goethe’s Way of Science by David Seamon: “…this reciprocity between darkness and light points to the ur-phenomenon of color: Color is the resolution of the tension between darkness and light. Thus darkness weakened by light leads to the darker colors of blue, indigo, and violet, while light dimmed by darkness creates the lighter colors of yellow, organize, and red. Unlike Newton, who theorized that colors are entities that have merely arisen out of light (as, for example, through refraction in a prism), Goethe came to believe that colors are new formations that develop through the dialectical action between darkness and light. Darkness is not a total, passive absence of light as Newton had suggested, but, rather, an active presence, opposing itself to light and interacting with it. Theory of Color presents a way to demonstrate firsthand this dialectical relationship and color as its result.”

First Sunday in Lent – February 14, 2016

First Sunday in Lent – February 14, 2016

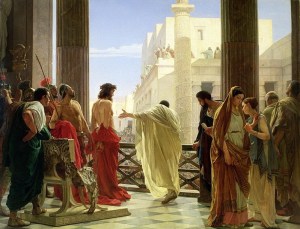

Rembrandt’s first painting was of the Stoning of Stephen. A close look at the faces of the crowd reveals at least three self-portraits of Rembrandt peering out from the crowd, just behind a prominent executioner with a large rock ready to pummel the praying Stephen’s head. Rembrandt saw himself there, close up and aghast, among the stoners but sympathizing, it seems, with the one being executed.

Rembrandt’s first painting was of the Stoning of Stephen. A close look at the faces of the crowd reveals at least three self-portraits of Rembrandt peering out from the crowd, just behind a prominent executioner with a large rock ready to pummel the praying Stephen’s head. Rembrandt saw himself there, close up and aghast, among the stoners but sympathizing, it seems, with the one being executed.