As I look at the structural violence symbolized by today’s funeral for Michael Brown in Ferguson and consider the Blackhawk helicopters from Fort Campbell, KY that turned Minneapolis and St. Paul, MN into an Army urban training ground last week, I’m remembering William Stringfellow with thanksgiving.

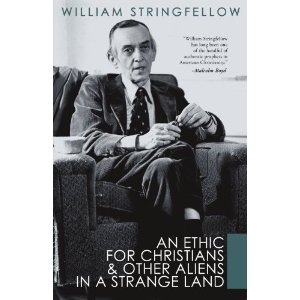

Bill Stringfellow was a thorn in the side of both church and state, a predictably unpredictable, lovable, hatable, tenacious, brilliant street lawyer, constitutional lawyer, and Episcopal lay theologian. The great Swiss theologian Karl Barth observed, during a speaking tour across the United States, that Stringfellow was the person who most captured his attention. If he were an American, he would listen to Bill. My copy of his most poignant work on the subject of what he called “principalities and powers” – An Ethic for Christians and Other Aliens in a Strange Land – was water-logged and mildewed because of a flood in the church basement, but his earliest book, My People Is the Enemy, sits prominently on my book shelf. He wrote the following from the one room, rat- and cockroach-infested tenement apartment in East Harlem where he had chosen to live and work among the poorest of the poor instead of accepting one of the New York law firm offers following graduation from Harvard Law School.

To become and to be a Christian is not at all an escape from the world as it is, nor is it a wistful longing for a “better” world, nor a commitment to generous charity, nor fondness for “moral and spiritual values” (whatever that may mean), nor self- serving positive thoughts, nor persuasion to splendid abstractions about God. It is, instead, the knowledge that there is no pain or privation, no humiliation or disaster, no scourge or distress or destitution or hunger, no striving or temptation, no wile or sickness or suffering or poverty which God has not known and borne for [humanity] in Jesus Christ. He has borne death itself on behalf of [humanity], and in that event he has broken the power of death once and for all.

That is the event which Christians confess and celebrate and witness in their daily work and worship for the sake of all [humanity].

To become to be a Christian is, therefore, to have the extraordinary freedom to share the burdens of the daily, common, ambiguous, transient, perishing existence of [humans beings], even to the point of actually taking the place of another [person], whether he be powerful or weak, in health or in sickness, clothed or naked, educated or illiterate, secure or persecuted, complacent or despondent, proud or forgotten, housed or homeless, fed or hungry, at liberty or in prison, young or old, white or [black], rich or poor.

For a Christian to be poor and to work among the poor is not a conventional charity, but a use of the freedom for which Christ has set [humanity] free.

~ William Stringfellow – 1964, My People is the Enemy [Anchor Book edition, p. 32.]

Thank you, Bill, for your wisdom, courage, and witness. We need it now as much as when you wrote it. “Lux aeterna luceat eis, Domine, cum sanctis tuis in aeternum, quia pius es. Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine; et lux perpetua luceat eis” (“May everlasting light shine upon them, O Lord, with thy saints in eternity, for thou art merciful. Grant them eternal rest, O Lord, and may everlasting light shine upon them.)”