“…Heaven have mercy on us all – Presbyterians and Pagans alike – for we are all somehow dreadfully cracked about the head, and sadly need mending.” — Herman Melville, Moby Dick.

Watching BBC/Netflix series The Fall — all three seasons in one huge gulp — led me to recall Arthur Miller’s play by the same title, the Genesis story, and the works of Herman Melville, William Golding … or even John Calvin. The brief appearance mid-way through the series of a 20£ bill with a note scrawled across it in red ink — He who does not love abides in death — and its unanticipated re-appearance in the series’ final scene seemed to this Presbyterian preacher like the subtext from which Allan Cubitt create The Fall.

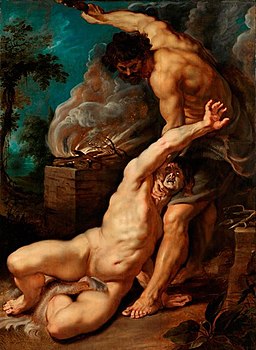

Great literature likeMoby Dick, and insightful sermons, films and television series are sometimes rooted in, and explicate, a text, a line, an aphorism. Allan Cubitt’s choice of the series’ title calls to mind Arthur Miller’s The Fall and the Hebraic biblical story of humankind’s attempt to master paradise by the raid on what belongs to the Creator alone — the knowledge of good and evil (Genesis 3:1-8) — that quickly results in fratricide between humankind’s first children.

Cain murders his brother Abel. Abel is blown away. Only Cain remains. But the echo of Abel’s horror remains to spoil the good earth: “Listen; your brother’s blood is crying out to me from the ground!” (Genesis 4:10). Allan Cubbit’s title points to the Genesis story. Likewise, his work, The Pool of Bethesda, is taken from Christian scripture.

Film critic reviews like Sophie Gilbert’s “Netflix’s ‘The Fall’ Comes to a Maddening End in its Third Season” (Nov. 5, 2016) in The Atlantic — express disappointment that The Fall “forgot” to answer “the questions [The Fall] raises about misogyny, madness, and obsession.” They see the bill as a glimpse into the deranged mind of Paul Spector, the serial killer, but nothing more.

The final scene of the final episode of the series begs for more. Stella, the detective who has cracked the case, has returned to solitude in her bloodless London flat. She pours herself a glass of red wine and reads again the red ink message: ”He who does not love abides in death,” the verbatim biblical quotation carefully plucked from the New Testament epistle that focuses on love as life itself, and lovelessness as death (I John 3:14). The note’s reappearance is more than a reminder of the bloody horror Stella seems to have escaped, or a return to the vexing inner workings of Paul Spector’s lethal psyche. It serves a larger purpose: to expose the series’ subtext, throwing a light backward on the inexplicable darkness and obsession with death and raising the question of Stella’s own loveless psyche and future, leaving the viewers to ponder for ourselves the complexities of love and life, lovelessness and death.

Works of art do not give answers. Neither does Cubitt’s The Fall. They do not explain reality; they describe it — the mystifying entanglement of lovelessness and love, of evil and goodness, the inexplainable complexity of all the sisters and brothers of Cain. Cubitt’s own reflection on the BBC calls attention to another scene midway through the series in which the serial killer’s Intensive Care nurse, Sheridan, tells him she will pray for him. “My idea is that the line ‘I will pray for you’ is provocative,” said the author. “Surely he is beyond redemption? It seems Sheridan [Spector’s ICU nurse] doesn’t think so. Has anyone ever prayed for Spector before?”

This and other scenes are, by design, “subtle and nuanced and ambiguous, open to all kinds of interpretations, replete with possibilities.”

“…and Heaven have mercy on us all – Presbyterians and Pagans alike – for we are all somehow dreadfully cracked about the head, and sadly need mending.”

― Herman Melville, Moby Dick.

— Gordon C. Stewart, a Presbyterian cracked head, Chaska, MN, April 15, 2019.